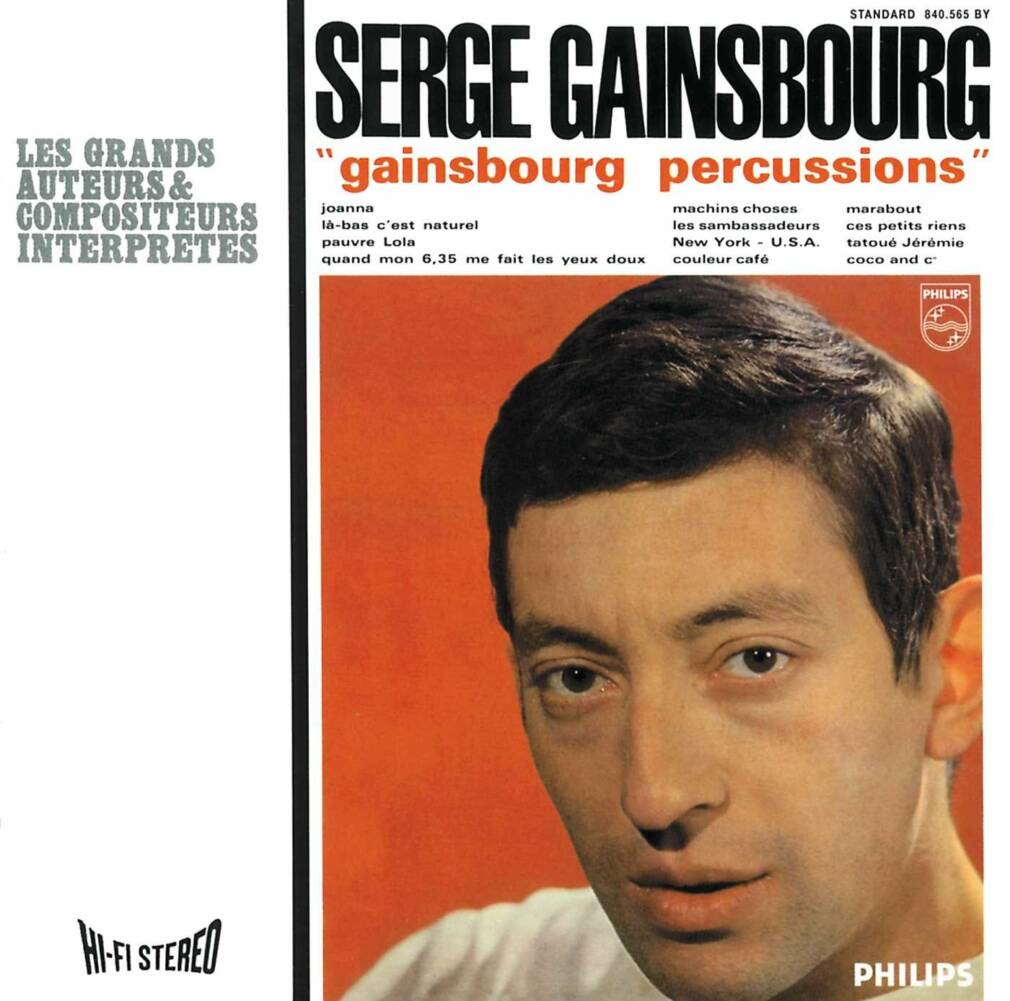

Was the French writer and composer out of ideas? Looking for a second wind? His sixth album, the avant-gardiste Gainsbourg Percussions, was largely “borrowed” from African artists whom he did not credit.

Serge Gainsbourg was on intimate terms with Western classical music: so intimate that his melodies were regularly inspired by them. But, in 1964, in the ground-breaking Gainsbourg Percussions, the French songwriter and singer did not borrow just from Brahms (among other composers), but from Miriam Makeba and especially from Babatunde Olatunji, who were both very much alive. Through the indirect route of a pop album, the two African artists joined the repertoire of French songs without knowing it.

On January 1965, invited on the popular music TV show Discorama, Gainsbourg declared: “I’ve heard a lot of guys who are still on the rive gauche (the intellectual singers and songwriters of the Latin Quarter in Paris, editor’s note), and who are going to starve that way. They’re not with it anymore.” His attempt to be “with it” was Gainsbourg Percussions, released three months earlier, the last of a series of six albums that were critical but not commercial successes. Gainsbourg was not yet the star he would become in the 1970’s and 1980’s. In fact, he was a middle-aged singer at a time when the audience to conquer was young people with their own music. France had surrendered to the rock coming from Liverpool, and listeners had become accustomed to the sound of drumbeats and the rawness of electric guitars. The record companies adapted to this: singers Johnny Hallyday, France Gall, Sylvie Vartan – who weren’t even twenty yet – were in fashion; they were nicknamed the “yéyés”.

Since Gainsbourg couldn’t pretend to be young in order to look like them, he became a songwriter for the young female “yéyé” singers on the record company he was signed to, Philips. But in order to be “with it”, he had a strategy, and in the summer of 1964, when the big hit on the radio was France Gall’s “N’écoute pas les idoles” (music and lyrics, Serge Gainsbourg), he convinced Philips to produce a sixth album with a surprising concept: an “African” album.

Drums of Passion

An album recorded by the Nigerian percussionist Babatunde Olatunji had given him the idea. Born in 1927 in Adijo, near Lagos, Olantunji had moved to the United States in 1957, where he soon was playing in clubs in New York with his percussion ensemble. He quickly became a success in New York’s black community, thanks in part to the political context: to listen to the music of Nigeria, and through it the music of the continent, was for certain militants a way to lay down the foundations of a shared Afro-descendent culture. Signed by Columbia Records, Babatunde Olatunji released his first album, Drums of Passion, in 1960.

The album features a selection of traditional Nigerian songs along with several original compositions. Four percussionists do the singing and the orchestration, in call and responses with a chorus of ten female singers. The quality of the playing, the reaction of the black American public, and the spectacular production in stereo made it a considerable success; and a notable milestone for black jazzmen as well. In 1962, as an homage to his friend, Coltrane wrote and recorded “Tunji” for Babatunde.

It was on a trip to New York that the French singer Guy Béart discovered Drums of Passion – through his friend Harry Belafonte. He took a copy back to France, where the album wasn’t distributed, and therefore still little-known. In Paris, he offered it to Claude Dejacques, the artistic director at Philips… who then gave the album to Serge Gainsbourg.

“The resulting logic of modern jazz”

Babatunde Olatunji’s percussion sounds had a huge effect on Gainsbourg. He knew that French popular songs were essentially based on melodies, to the detriment of rhythm. But by then percussion had barged in through imported music such as jazz and rock. The drums now imposed their rhythms once and for all. Through all these transformations Serge was looking for a new way to please the public. Drums of Passion could represent this third way in modern music: neither jazz nor rock, but “African”. As he put it on a radio show on France Inter at the time: “I’m not disoriented, I’m very Africanized.”

“I felt that it was the resulting logic of modern jazz”, headded, since Drums of Passion is an essentially rhythmic album, where the singing accompanies the percussion rather than the other way around.

When he saw Claude Dejacques again, Serge pitched his idea to acclimatize the French public to this African “avant-gardism”. He had been compiling a rich corpus of references based on the curiosity initially kindled by Drums of Passion, starting with Miriam Makeba, whose albums were distributed in France. And he was well aware that in America black jazz musicians were focusing more and more on Africa: Louis Armstrong had done a tour there. Duke Ellington hadn’t yet, but he had already composed “Fleurette Africaine”; and Cannonball Adderly had written African Waltz (which Serge learnedly played on the piano on a TV show in 1965).

On the same TV show, a song by Xavier Cugat, the guru of American mambo, was featured, which inspired Serge to explore Caribbean rhythms. Harry Belafonte had also caught his attention: he translated the lyric “Once again now” from the song “Matilda” on the last track of Gainsbourg Percussions.

This eclecticism was in fact not unusual at the time. Contacted by PAM, Michel Portal, who played alto on the album, insists on the enthusiasm of French jazz musicians for all the music that arrived in Paris from America of course, but also from Africa. “There was a lot of African music that was coming from all over. We were very well aware of what music was coming from Senegal or from the Central African Republic. We listened to everything, there was so much incredible music everywhere.” In the microcosm of Parisian jazz, the Gainsbourg Percussions project and its eclectic references were not uncommon, especially since studio musicians were accustomed to playing in various styles. “When we played at recording sessions,” remembers Portal, “We were often asked to play a song in this style or in that style…”. In this context, the musicians had to adapt to the references Gainsbourg brought to the studio. “I already knew Makeba’s music and others”, states Portal. “So I said to myself , ‘Hey, if we’re doing this with Gainsbourg, we can’t just do anything’.”

So, with the support of Dejacques, and with a renewed credibility after his recent hits as a songwriter (but not as a singer), Gainsbourg was given a decent budget by Philips, and a week of recording sessions at the Studio Blanqui in Paris.

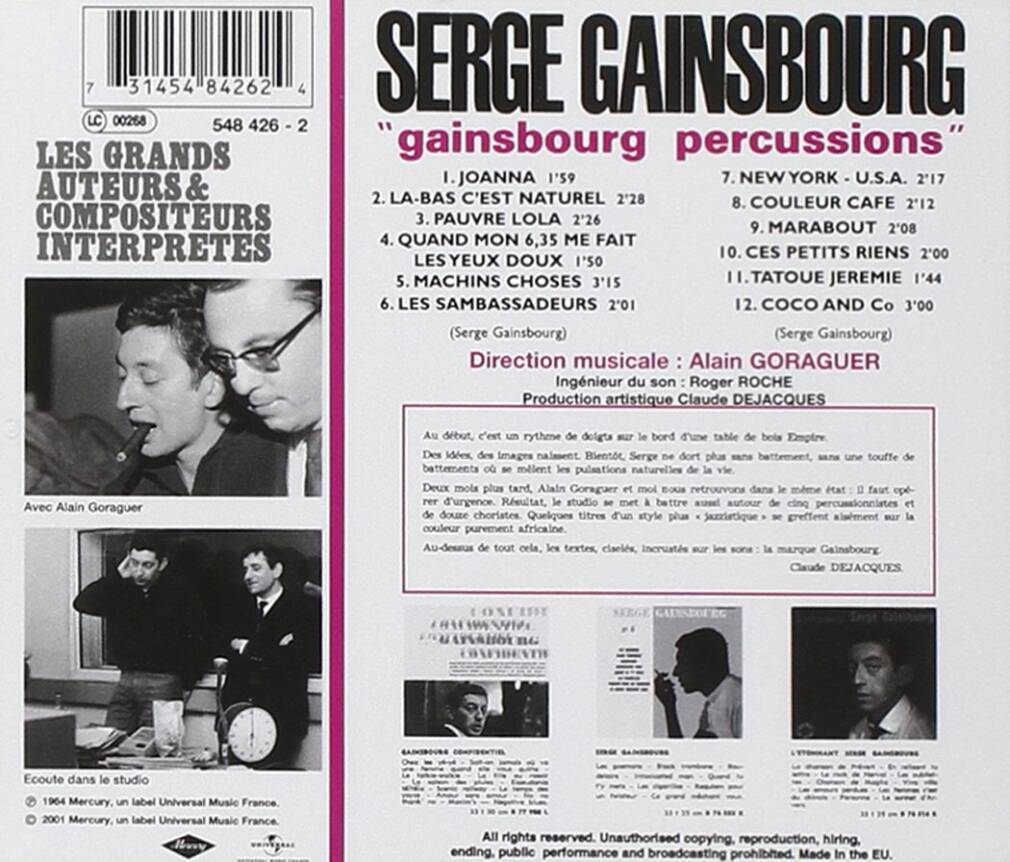

Gainsbourg Percussions, Gainsbourg counterfeits

On October 5, 1964, Serge arrived at 94 boulevard Blanqui, in Paris’s thirteenth arrondissement. It was the first day of recording sessions for the instrumental tracks in Gainsbourg Percussions. All his songs were ready, he had the whole album in his head, and he had written some of the melodies, such as “Couleur Café”; the pianist Alain Goraguer, the second architect of the product, had written the arrangements. They hired a choir, several jazzmen, and for the rhythms Serge hired a musician from Lyon, André Arpino, who played drums at the Lido. It was Arpino who was in charge of the percussion section, the cornerstone of the album. As for the musicians involved, Gainsbourg later stated: “I could bluff and say that they’re black, as people might believe, but it’s not true.”

In the studio, Goraguer and Gainsbourg shared a secret, some of the songs weren’t composed by Serge. Three of them came directly from Drums of Passion. As for the arrangements, Goraguer basically copied as closely as possible the original recordings, just as Gainsbourg did to set the metrics for his lyrics. Goraguer also used “Umqokozo” by Miriam Makeba, whose guitar riff is reproduced in “Pauvre Lola”. In addition to these four plagiarisms, the album also included three original songs also inspired by Gainsbourg’s research, where Afro-Cuban percussions replaced the drums, as well as several bossa, samba and jazz tunes in which the drums are sometimes enhanced with percussion.

According to Arpino (cited in Le Gainsbook, dir. Sébastien Merlet, Seghers 2019), only the trio Gainsbourg-Goraguer-Dejacques, and perhaps the recording engineer at the Studios Blanqui, knew about this. The musicians weren’t aware of the plagiarized albums, that the copied rhythms were first transcribed by hand, then put on paper for the percussionists recruited by Arpino to play. In other words, Gainsbourg and Goraguer knew they were plagiarizing and were hiding it. When promoting the album when it was released, Gainsbourg never mentioned Olatunji, instead evoking – with an unfortunate and rather typical confusion for the time – “rhythms from Nigerien folklore”, or “African records, Nigerien folklore, Kenya, all that…” (sic). He mentioned Makeba once, during an interview on France Inter. But for the accounting records of the SACEM all the credits – at the time – went to Serge Gainsbourg.

“Life’s natural pulses”

On the back cover of the album, released on October 26, 1964 is this quote from Claude Dejacques:

“First, it’s the rhythm of fingertips on the edge of an Empire table. Ideas, images emerge. Soon, Serge is no longer sleeping without these pulses, without a cluster of beats merging with life’s natural pulses.”

A curious way to describe the abundant nature of life and all that is thrilling about it. The fantasized Africa of sensual, ahistorical and colonial imagery is found paradoxically on the back cover of an album whose ambition was to demonstrate the cutting-edge modernity of African music to the French public. In fact, Gainsbourg had nothing to do with the album art. Philips, worried about the overly avant-garde aspects of the album, tried to make it look more commercial with irrelevant artwork and a questionable quote that the general public, used to a certain vision of Africa, would understand.

And yet throughout the album Gainsbourg’s lyrics alternate bizarrely between daring avant-gardist touches and the use of the same old tired colonial fantasies. The track “New-York USA” (which plagiarizes “Akiwowo” by Olatunji), whose lyrics include a surprising list of buildings in New York, is already a manifesto for a new type of French song. On the other hand, in songs like “Là-bas c’est naturel” (“Over there it’s natural”), Gainsbourg forgets his intellectual audacity and modulates instead towards the supposed sensuality of African women.

Over there it’s natural

“Là-bas c’est naturel“

Over there in Kenya

For all the natives it’s OK [Kenya was chosen only for the play on words]

All the women wearing a two-piece minus one

Everyone in this black paradise, in a monokini.

Did Gainsbourg realize his ambitions with Percussions? The public said no, the record did not sell. Which isn’t a surprise, since the album was so unusual for the time. And yet the avant-gardist stance behind the project was not followed through rigorously. The artist was walking a fine line between a true appreciation for African rhythms and the lazy meanderings of exotica. On some of the songs he lapses into kitsch, to the detriment of his credibility. And the plagiarization of the songs that punctuate the album don’t help either.

For Michel Portal, Gainsbourg, obsessed with rock, demonstrated during the sessions for Gainsbourg Percussions an evident artistic indecisiveness. “We wondered if Gainsbourg wasn’t already going in other musical directions that were appearing at the time. All the music he later recorded that I listened to – Jane Birkin, etc – I said to myself: ‘But what were we doing at the time?’ We felt it in the studio.” As if Serge had admitted to himself that his African escapade had been nothing but a whim. “I heard him playing the piano. He wasn’t in Africa anymore, he was somewhere else…”

Indeed, the next album was resolutely rock and had no African references. Initials B.B.,made the singer a star four years later. Gainsbourg Percussions became a hit when it was reissued years later, after Gainsbourg had become a huge star and his entire back catalog was seen in a new light. Inevitably, Columbia Records confronted Philips about the plagiarism issue in the 1980’s. An agreement was reached at the time. Olatunji is now credited as the composer (or the arranger, some of the themes are traditional Nigerian songs) of three stolen songs. As for Makeba, she never claimed her rights.